Optimizing Performance and Cost with Multi-AZ Architecture: Guidelines for Multi-Account Environments

This post provides some guidelines and considerations on using multiple Availability Zones in a multi-account, multi-VPC environment.

Image not found |

|---|

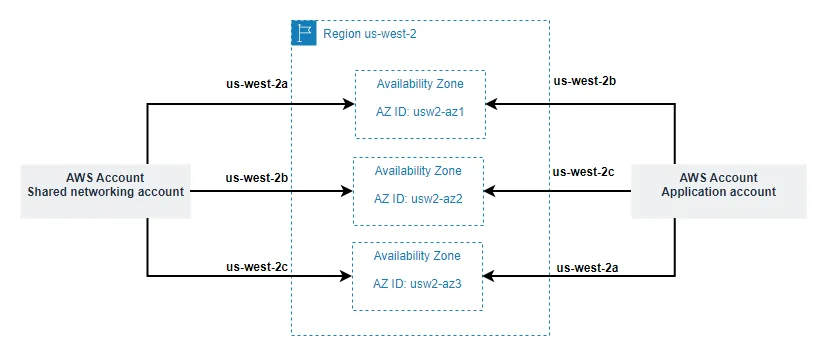

| Figure 1: Multi-Account/Multi-VPC deployment architecture |

Image not found |

|---|

| Figure 2: East-West (VPC-to-VPC) traffic inspection scenario |

Image not found |

|---|

| Figure 3: Availability Zone Name (create VPC) |

|

|---|

| Figure 4: Availability Zone Name – Availability Zone ID mapping example |

- Navigate to the AWS (AWS Resource Access Manager) (RAM) console page in the AWS console.

- You can view the AZ IDs for the current AWS Region under Your AZ ID. Alternately, you can also go to EC2 Dashboard in the console for the respective region and see the AZ IDs listed under the Zones section.

Image not found |

|---|

| Figure 5: Determining the AZ IDs for an account in a given region |

Image not found |

|---|

| Figure 6: Traffic flow from the application server to the domain controller. |

- Traffic from the application server in AZ-A VPC-A is sent to the Transit Gateway for destination in VPC-B AZ-B. The default route (0.0.0.0/0) in Application VPC A route table is used. Traffic is sent to the Transit Gateway Elastic Network Interface (ENI) in AZ-A due to the Transit Gateway AZ affinity.

- The Transit Gateway uses the default route (0.0.0.0/0) of pre-inspection route table pre-inspection route table's default route (0.0.0.0/0) to route traffic to the Inspection VPC C in the shared networking account as the Application VPC A attachment is associated with the pre-inspection route table.

- In this example, we assume that the Transit Gateway has selected the Transit Gateway ENI in AZ A in the Inspection VPC for this flow. The traffic is sent to Transit Gateway ENI in AZ A.

- Traffic is routed to the AWS Firewall Endpoint in AZ A based on the (0.0.0.0/0) on the route table of the TGW attachment subnet ( AZ A - TGW subnet route table) in the Inspection VPC. Here we are using routing to maintain the AZ affinity.

- Based on the default route (0.0.0.0/0) in the Inspection VPC C route table, the traffic to Transit Gateway routes traffic to the Transit Gateway ENI in the same AZ (AZ-A).

- The Transit Gateway uses the default route (10.2.0.0/16) in the post-inspection route table to route traffic to the Shared services VPC, as the Inspection VPC C attachment is associated with that route table.

- Due to the stickiness behavior enforced by enabling the appliance mode on the Transit Gateway, the traffic is sent to the TGW ENI in AZ A in the Shared services VPC as the source is in AZ A.

- Traffic is routed to the destination based on the route (10.2.0.0/16) in the VPC B route table. The AZ change happens here.

Image not found |

|---|

| Figure 7: Return traffic flow to the Application Server to the from the Domain Controller. |

Image not found |

|---|

| Figure 8: Routing traffic through NAT Gateway. |

Image not found |

|---|

| Figure 9:AZ aware load balancing scenario |

- Traffic from the Internet flows in through the Internet Gateway to the Elastic IP address of the ALB, which is dynamically created when you deploy an Internet-facing ALB.

- The ALB is associated with one public subnet in each AZ. The ALB uses its internal logic to determine which ALB ENI to send traffic to. It is here where the cross-zone load balancing setting plays an important role. If cross-zone load balancing is disabled, then the ALB will send the traffic to an ALB ENI in the same AZ as the target endpoint. If not, then ALB can send the traffic to an ALB ENI that is in an AZ different from the AZ target endpoint. This scenario is further explained in step 10 below.

- Traffic is sent to the Transit Gateway based on the VPC E route table default route.

- Since the Ingress VPC E attachment is associated with the pre-inspection route table, the Transit gateway uses the default route (0.0.0.0/0) to route traffic to the Inspection VPC.

- As the appliance mode is enabled on the attachement to the Inspection VPC, the Transit Gateway will select one of the Availability Zones to keep for both direction of the flow. We assume here that the traffic is sent to the attachment TGW ENI in the same AZ (AZ B).

- The traffic is routed to the AWS Network Firewall Endpoint in AZ B based on the routing table of the AWS Firewall subnet in AZ B.

- Based on the default route (0.0.0.0/0) in the Inspection VPC C route table, the traffic to the Transit Gateway is sent to the local (same AZ) Transit Gateway ENI in AZ-B.

- Since the Inspection VPC C attachment is associated with the post-inspection route table, the Transit gateway uses route (10.1.0.0/16) to route traffic to the Application VPC.

- Due to the Availability Zone affinity behavior of the Transit Gateway, the traffic is sent to the TGW ENI in Availability Zone B in the Application VPC as the source is in AZ B.

- Traffic is routed to the destination based on route (10.1.0.0/16) in the VPC A route table. With cross-zone load balancing disabled, traffic will be kept in the same AZ. In this particular scenario, we have added the Inspection VPC with the appliance mode enabled to the path. This configuration may lead to the Transit Gateway selecting a different AZ for traffic inspection. However, with cross-zone load balancing still disabled, we can minimize the frequency at which traffic crosses AZ boundaries This is possible because the ALB will select an ALB ENI in the same AZ as the destination, as explained in Step 2. If you enable the cross-zone load balancing, traffic can be sent to an AZ different from the ALB ENI AZ. Flow 10a illustrates this scenario.

Any opinions in this post are those of the individual author and may not reflect the opinions of AWS.