Four Things Everyone Should Know About Resilience

Dive into these essential concepts for building resilient applications in the cloud on AWS.

- Use fault isolation to protect your workload (Well-Architected best practices).

Required Lambda Concurrency = Function duration X Request rate

- Design your workload to adapt to changes in demand (Well-Architected best practices).

- Performance architecture selection (Well-Architected best practices).

- Using trade-offs to improve performance (Well-Architected best practices).

This was a real bug I had to fix here for my chaos engineering lab that would cause processes to lock up when the database failed over from primary to standby.

- Design for operations: Adopt approaches that improve the flow of changes into production and that help refactoring, fast feedback on quality, and bug fixing (Well-Architected best practices).

- Design your workload to withstand component failures (Well-Architected best practices).

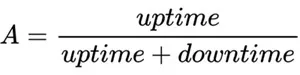

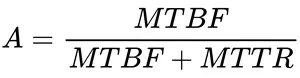

- MTTR: Average time it takes to repair the application, measured from the start of an outage to when the application functionality is restored.

- MTBF: Average time that the application is operating from the time it is restored, until the next failure

- Disaster Recovery (DR) Architecture on AWS (blog post series)

- Design Telemetry (Well-Architected best practices)

| High Availability (HA) | Disaster Recovery (DR) | |

|---|---|---|

| Fault frequency | Smaller, more frequent | Larger, less frequent |

| Scope of faults | Component failures, transient errors, latency, and load spikes | Natural disasters, major technical issues, deletion or corruption of data or resources, that cannot be recovered from using HA strategies. |

| Objective measurements | Availability ("nines") | Recovery Time Objective (RTO), Recovery Point Objective (RPO) |

| Strategies used | Mitigations are run in-place and include: Replacement and fail over of components or adding capacity | Mitigations require a separate recovery site and include: Fail over to the recovery site or recovery of data from the recovery site |

- AWS Fault Isolation Boundaries (whitepaper)

- Deploy the workload to multiple locations (Well-Architected best practices)

- AWS Resilience Hub is an AWS service that provides a central place for assessing and operating your application resiliently

- AWS Fault Injection Simulator is a managed service that enables you to perform chaos engineering experiments on your AWS workloads.

- AWS Elastic Disaster Recovery enables reliable recovery of on-premises and cloud-based applications.

- Building a Resilient Cloud: 6 Keys to Redundancy in AWS covers both HA and DR and how to implement them.

- Resilience analysis framework is a framework to continuously improve the resilience of your workloads to a broader range of potential failure modes in a consistent and repeatable way.

- Shared Responsibility Model for Resiliency shows you how resilience is a shared responsibility between AWS and you, the customer. It is important that you understand how disaster recovery and availability, as part of resiliency, operate under this shared model.

- Availability and Beyond: Understanding and Improving the Resilience of Distributed Systems on AWS outlines a common understanding for availability as a measure of resilience, establishes rules for building highly available workloads, and offers guidance on how to improve workload availability.